The UK steel industry: how and why decarbonization has failed

Ill-conceived public policy has created obstacles to the green transition

The UK economy is steadily moving towards zero CO2 emissions. Against this background, its steel industry looks like a clear outsider. However, this is not the fault of local steel companies. The rules of the game are dictated by the state. That is why the British case looks like an example of how NOT to decarbonize the steel industry.

A problematic transition

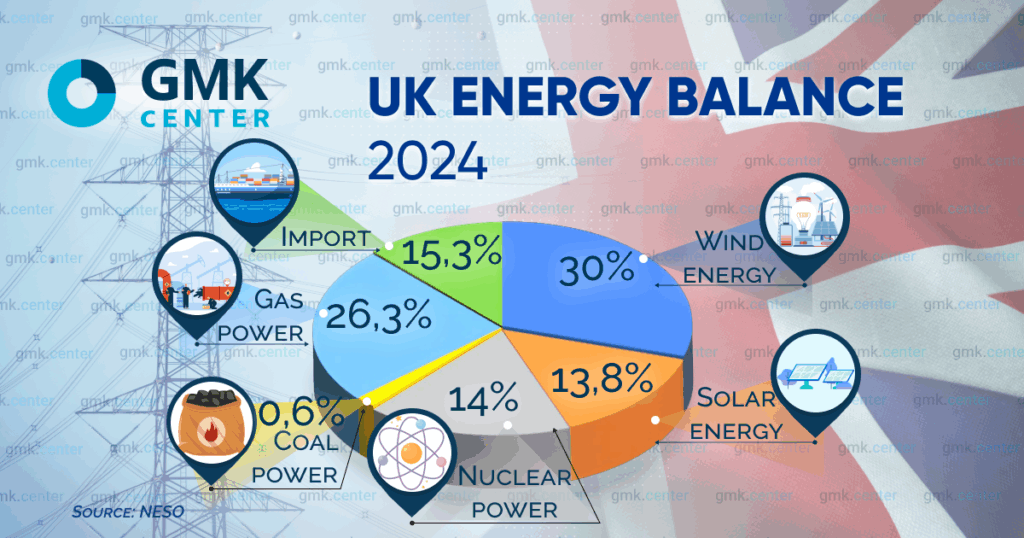

Last year was a historic year in the British energy industry. At the end of September, the Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station in Nottingham – the last coal-fired thermal power station in the country – closed. Wind for the first time became the largest source of electricity (ee) generation, with its share in the energy mix growing by 2% year-on-year.

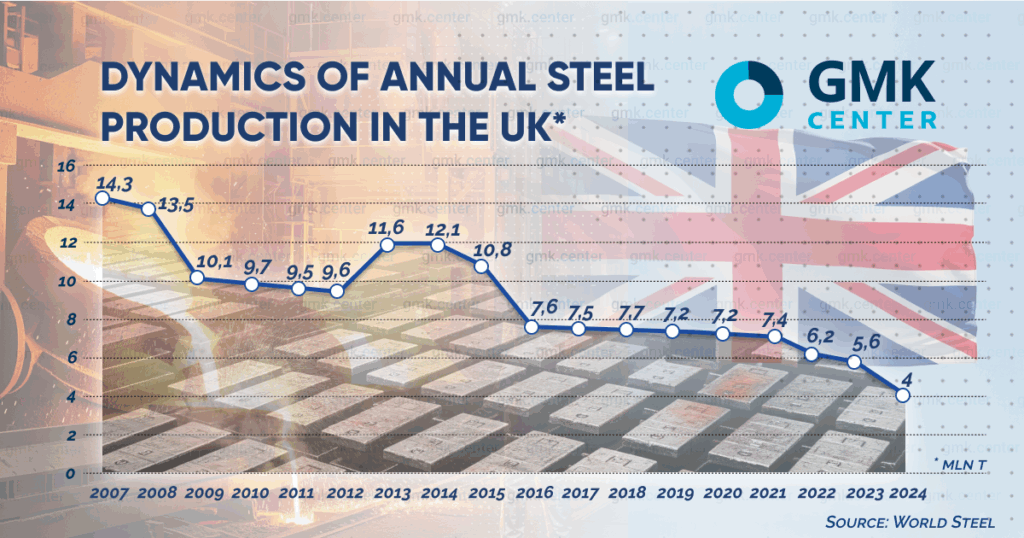

This means that steel companies can significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions through renewable energy sources (RES). Nevertheless, until recently, the largest steel companies were present in the top 10 of the UK’s biggest CO2 emitters. Port Talbot mill, owned by India’s Tata Steel, is in 4th place with 6.2 million tons in 2023, while British Steel’s Scunthorpe mill is in 8th place with 3.3 million tons. The emissions of the entire British steel industry in 2023 are 9.862 million tons.

Why is this so? Because the switch from BF-BOF to EAF scrap based proved too painful for the owners of Port Talbot and Scunthorpe. The cost of building an EAF at Port Talbot is £1.25bn, at Scunthorpe it is over £2bn, and the investment opportunities of the producers themselves are limited by narrow margins. This, in turn, is a consequence of the weak protection of the domestic market from cheap steel imports.

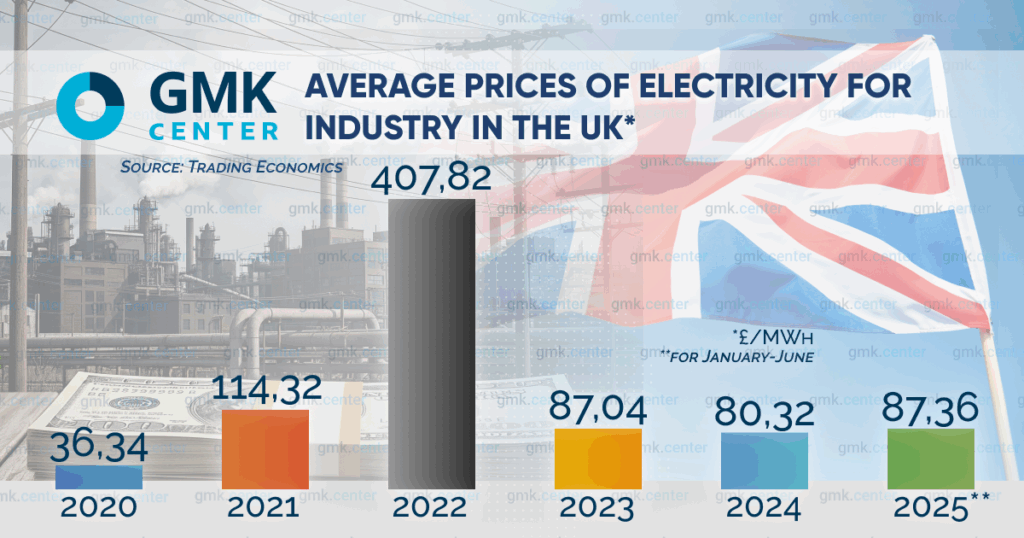

One should also add the high cost of electricity. Yes, the situation looks better now than a few years ago.

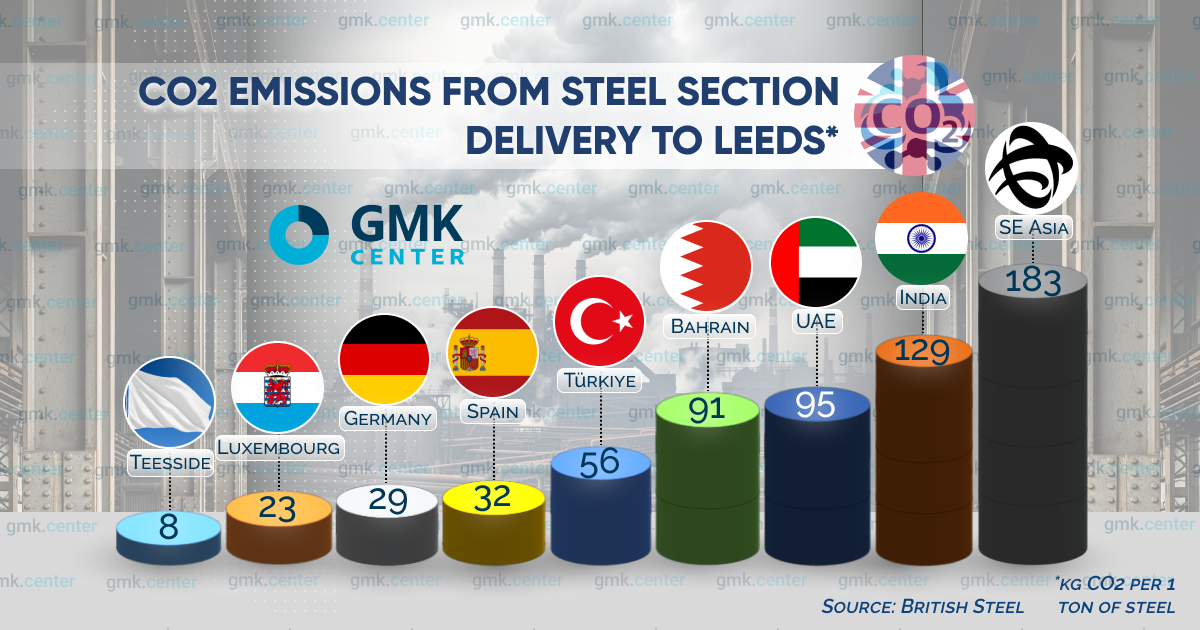

However, even now, green energy in the UK is 60% more expensive than in European countries, according to the UK Metals Council. That is, the owners of Port Talbot and Scunthorpe have a clear understanding that their investments in the EAF crossing are unlikely to pay off. But it is also unprofitable to continue operating BF-BOF due to the high cost of CO2 permits. A stalemate situation requiring state intervention. And the state has intervened.

The government agreed to provide £500m to build the EAF at Port Talbot. Plus £80m for a compensation program because the project will result in the loss of 3,000 jobs. From October 1, 2024, blast furnace production at the plant ceased, and the EAF is scheduled to start up in 2027.

Here, the government also offered the owner, China’s Jingye Group, £500m for the EAF transition. But the company declined because the government’s shareholding would have been less than in the case of Port Talbot: 25% versus 40%.

As a result, British Steel went into temporary state administration on April 12 this year. At the same time, Secretary of State for Business and Trade Jonathan Reynolds said that the authorities are ready to independently finance the creation of electric steelmaking at Scunthorpe. He said £2.5bn has been set aside in the Sovereign Wealth Fund for this purpose.

From the point of view of prudent use of public funds, this is a strange decision to decarbonize: to take on the entire £2 billion cost instead of splitting it in half with the Chinese. Who may also have to pay liquidated damages after international arbitration. Since Jingye Group hired law firm Linklaters in early June to work on recovering the money spent on British Steel.

And it should also be remembered that by taking responsibility for British Steel, the government has “pinned” the problem of future subsidies for its production on the British budget. Since the problem of the high cost of “green” electricity for EAF has not gone anywhere.

But, be that as it may, it can be stated: this year CO2 emissions in the British steel industry will be reduced by almost 70% due to the closure of blast furnaces of Tata Steel UK. And if the construction of the EAF in Port Talbot and Scunthorpe goes according to schedule, in 2-3 years the UK will completely stop exporting steel scrap. As early as 2024, this amounted to 7.6 million tons.

This is a good reason for Ukrainian officials to think about how to ensure decarbonization of the Ukrainian steel industry in conditions when domestic scrap is already on the verge of shortage. And the availability of imported scrap is getting narrower and narrower.

But let’s return to the British steel industry. Since the mid-2000s, steel production in the United Kingdom has fallen by half. On the one hand, CO2 emissions have also fallen by more than 3 times. On the other hand, this is evidence of systemic problems in the industry unrelated to green transformation. Deindustrialization is not the path to sustainable development.

The UK’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) calls for zero CO2 emissions by 2050 and an 81% reduction (compared to 1990) by 2035.

Tata Steel UK and British Steel claim that after the EAF transition their emissions will be at 0.85 tons per 1 ton of steel. Taking into account that under BF-BOF production they were 2.4-2.6 tons – we can say that the reduction will be about 70%. But this is already by 2030, if the implementation of projects does not drag on. Further reductions will obviously require the introduction of CCUS.

Other British steel producers are already using EAF and their specific emissions are very low. For example, GFG Liberty Steel Rotherham, with a capacity of 1.98 million tons of steel per year, has 0.4 tons, according to the company. 7 Steel UK Cardiff (formerly Celsa Steel UK) with a capacity of 1.2 million tons has 0.417 tons, also according to the company. That is, they have nothing to worry about until 2035. And then – the same CCUS, full transition to RES and H2-DRI.

But so far, producers have no such concrete plans. And some of them are clearly not in the mood for it now. For example, Liberty Steel’s plants in Rotherham and Motherwell have been idle for a year now. The reason is the debt crisis of Sanjeev Gupta’s company. And the consequent lack of working capital for operations.

Tata Steel UK has indicated in its roadmap that it is willing to consider building a 2 million tpa DRI plant – subject to financial support and a favorable business environment. These include access to competitive natural gas and then to green hydrogen, which is not currently available.

Indeed in the UK there are currently no H2-DRI pilot projects either under development or under implementation. By comparison, there are 23 such projects in the EU, according to the UK government. The high cost of electricity in the UK is cited as the reason why companies do not want to invest in this area.

In the case of a complete transition of existing steel mills to hydrogen technologies, 1 GW of capacity is needed to cover their H2 needs. The UK hydrogen strategy envisages 1 GW by 2025 and 5 GW by 2030. At present, there is no such capacity, i.e. the British have failed to fulfill Stage I. And there are no preconditions to catch up in the next 5 years.

British Petroleum has an interesting project to build a 500 MW HyGreen Teesside plant. This figure was planned to be reached by 2030, and this year the first 80 MW module was to be commissioned.

Products from this plant could have been sourced from British Steel’s future electric steel smelter at Lakenby, in the Teesside Industrial Estate. But. so far this plant is only in British Steel’s presentation materials. Oh, and British Petroleum officially announced in March this year that HyGreen Teesside has been “frozen” indefinitely.

Similarly with CCUS. Previous governments have twice tried to launch CCUS in the UK. But those programs were canceled in 2011 and 2016. The current approach, launched in 2018, aims to create 4 CCUS clusters. The fact is that these are too large-scale and expensive projects for a single company. Therefore, it is proposed to combine a number of industrial companies from different sectors for transportation and storage.

The authorities set a goal of capturing and storing 20-30 million tons of carbon per year by 2030. In December 2024, the Ministry of Energy and Net Zero concluded that the target was not achievable. It has yet to set revised targets. However, at the same time, in December 2024, the Department of Energy announced the signing of contracts with the first two projects in the East Coast cluster, which includes Teesside and Humberside.

They are expected to be operational in 2028. But it cannot be asserted now that this will be the case, given previous negative experiences. Even despite the financial support of £21.7 billion over 25 years declared in March 2023 by the British Treasury.

Hope for CBAM

The only thing that is certain is that the announced EAF transition in the UK steel industry will still take place around the announced timeframe. As noted, there are already opportunities to provide it with clean electricity. The problem of affordability remains to be solved. Because there will be no decarbonization without cheap and affordable electricity. Only large capacities can provide it. Actually, this applies not only to the UK, but also to other countries. Including Ukraine.

That is why the British government pursues the goal of further expansion of RES infrastructure. The National Action Plan «Clean Energy 2030» envisages a significant increase in installed RES capacity over the next 5 years. Increasing the supply of green energy should reduce its cost, in line with market laws.

The UK Green Energy Program envisages an increase in capacity by 2030:

- Onshore wind power to 29 GW, up from 15.7 GW in 2024;

- Solar power to 45 GW, up from 18 GW in 2024;

- Offshore wind power to 43 GW, up from 14.7 GW in 2024;

Secondly, the introduction of CBAM UK, scheduled for January 2027, will significantly limit the access of imported steel to the UK market. Preliminary calculations by British Steel show that in such a case, at the expense of Scope 3, even clean steel from the Gulf will not be able to compete with local steel.

In this case, British producers will be able to increase their sales margins and volumes. This, in turn, will make it possible to painlessly buy green electricity for production needs. And rising prices for steel products will make it possible to pass these costs on to end consumers.